- Home

- Feryal Ali Gauhar

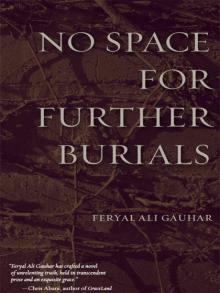

No Space for Further Burials Page 3

No Space for Further Burials Read online

Page 3

I found some interesting objects in the office. There is a register with the names of the inmates and the afflictions which caused them to be incarcerated here. There is another register of provisions, none of which exist anymore, and a small notebook belonging to the doctor who ran this place, a Canadian, if I am to go by the maple leaf embossed on the diary. This must have been the man who owned the Sears catalog. There are photographs of a woman and three small children in front of a Christmas tree and a log fire. These I found tucked into the fold of the diary. There is another picture of a man and a woman, the same woman, holding each other against the red and gold of autumn in the hills somewhere. There is a lake in the background. I can see the water clearly, I can smell the wet scent of the woods, I can hear the crackling of dry leaves.

Bulbul called me out of the office just when I was beginning to try to piece together the life of the Canadian doctor. I could tell from the shrill tenor of his voice that something was wrong. I rushed out and saw him come toward me, his scarf trailing behind him like the skin of a slaughtered animal. Zood bia, come quickly, he said and grabbed my hand. He was pulling me toward the cell where the only female inmates of this asylum were housed. I had never been there, even when Noor Jehan wanted me to look at the young girl who refused to eat or sleep, staring out of an opening set high in the wall of the cell. I did not know what to expect, and feared only more confusion and the incredible weight of my own helplessness.

Bulbul urged me into the cell. His hands were caked with clay, and streaks of muddy sweat cut rivers into his face. He had rolled up the ends of his jeans and I saw deep scars on his legs, burn marks, stains against his skin. There was no time to ask him about them, he was pushing me into the cell and repeating to himself the words, “Ya Khuda, ya Khuda,” Oh God, oh God.

It was dark in the cell, the light from the vent hardly enough to guide me toward the corner where a woman crouched, huddled in a dark shawl. She was small, I could not tell whether she was old or young, she had her head covered with that shawl and her hands, clenched into fists, were clutched against her chest, the curled claws of dead sparrows. Bulbul walked toward her gently, as if he was approaching an injured creature. He signaled me to follow slowly, using his hands to convey the gravity of our mission.

For a while he just stood over that figure, staring at the woman, frozen like a corpse in winter. Then he bent down and placed one hand on her shoulder, softly. The woman did not move. Bulbul began to speak to her, repeating her name over and over again: Anarguli, Anarguli.

It was only when he sat down beside her on his haunches that he began to speak to her with other words, tender words, ones I could not understand except for the solace they carried to this unknown person hiding beneath that grimy shawl. She did not speak, she just unfurled one of her hands as if it was a flower, the bloom of the pomegranate tree for which she was named. She held out her hand to Bulbul. I watched him as he looked at her palm and carefully brushed into his hand the tiny red beads she held within. Then he held her hand and said one word to her. Tashakur, he said, thanking her for the gift.

Bulbul stood up after a while. There were tears in his eyes that he tried to wipe with a muddy hand. His red scarf hung limp like a broken tail.

I could hear the soft sigh of grief as it drifted out from the crevices in the walls of that cell and settled on us like a mantle.

It is evening now. The day’s work has been done. My back feels as if it has been broken in two, my hands are blistered and bleeding, the rawness of the wounds burning into my palms. It is difficult for me even to hold this pen, and as I write, the blisters spill fluid onto the paper, smudging the words which in any case don’t seem to have any shape in this fading light, this place of amorphous shapes and meaningless sounds.

Noor Jehan is treating us to potatoes roasted in the clay oven. There are enough for everyone in the compound, and Qasim the boy has even managed to flavor his with some cumin seeds he says he found in the basement where provisions are stored.

Waris looks at the boy as the child indicates the basement with a nudge of his head. Then he looks at Sabir, then at Noor Jehan, and then they are quiet. I don’t know what any of this means. I want to eat this potato and then crawl into my cell and fall asleep under the lumpy quilt Bulbul salvaged from somewhere. Somehow he manages to find things amidst this desolation as if he was actually shopping at the Riverside Mall in Fresno. He never ceases to amaze me, and this evening when I saw him with that woman in the cell, I realized she must be the one whose picture he drew on the wall and kissed with so much passion.

October 12, 2002

Last night, when all I wanted was to sleep, to shut out the reality of what has come to pass, I found myself listening to Bulbul’s story which he told me with words he made up as he spoke, words from his heart, from the deep tunnel of his longing. I believe I have been here for almost a month now; autumn is closing into winter. In these long days and nights I have begun to understand this young man who speaks with his eyes and his hands, and a tongue which weaves terrible stories.

Bulbul sat beside me on the burlap sack I use as a thin mattress covering the bare floor. He was unable to speak for quite a while, and in the blue darkness I could barely make him out as he sat, leaning against the pock-marked wall as if he was waiting for some signal to begin his tale.

I could have fallen asleep, perhaps I had. It was the sound of his sobbing which brought me back. He reached out for me and pulled my hand toward him. I wasn’t sure of his intentions, but sleep had turned my limbs into pillars weighed down with lead. I let him guide my hand to his leg, and pulled away only when he began to raise the cuff of his jeans, rolling up the soggy denim where the caked mud had stained it and made it heavy. I didn’t know what he wanted, and fearing the worst I pulled my hand away. He didn’t speak for a while, and when he did he spoke through a voice strained with sorrow.

My father was a farming man in a village far from here, beyond the shadow of these mountains. We had some land in that village, Sarchashma, named for the water which sprang out of the earth and nourished the fields. We grew corn and sugarcane and it was hard work trying to farm that land, but we had enough to eat and we lived with dignity.

It was after the war that things changed quickly for us. My father went into the fields one day to harvest the corn. The leaves on the trees were changing color, and birds had started leaving for warmer places. I was so young then, perhaps six or seven. I remember I had lost my front teeth that year, and my mother kissed me and told me that there was now a window in my mouth, so I could look out at life and become all that she had dreamed I would be. She said that I was growing up to be a fine young man, strong enough to help my father on the land.

I had a younger sister, Gulmina, just three or four then. Mina, we called her. It means love in my language. And Gul, it means flower—so she was the Loved Flower, or maybe she loved flowers, I don’t know—I don’t even know where she is now, or if she is, or if she is among the flowers for which she was named.

That day when my father did not return from the field, my mother asked me to go and get him—it was that time of day when the sky turns the color of a ripe peach and the sun begins to settle into its bed beyond the mountains. I had herded our few sheep and the cow into the shed and was waiting impatiently for the meal my mother had cooked that day. Wild spinach, yes, it was wild spinach. And bread, made from our own corn. We even had some buttermilk from the cow who had calved the previous year—we lost that calf, I remember it still, I had named it Spozhmai, full moon, because it was white and lay curved into a circle beside its mother.

Spozhmai was born in the winter. We did not have enough fuel to keep her warm, so we brought her into our own room where my mother would hold her close to us when we slept. But the winter was very cold that year, made bitter still by the fact that the trees we chopped for kindling had been destroyed in the bombing, and those that survived had been felled by the government which said the rebels hid in these t

rees that gave us fruit and shade in the summer and warmth in the winter.

So Spozhmai did not live out the winter, and then my father had that accident in the field. He said he never even saw it, the mine that blew off his legs. He had been picking heads of corn from their stalks to store for the winter—my mother would beat the kernels off the cob, and even my sister would help to gather them from the patch of earth outside our home. Often we would roast the stray kernels and have them as a snack. Sometimes my mother would add a bit of molasses to the corn—my father made the molasses from our own sugarcane, adding almonds and raisins to it for special occasions, like his brother’s wedding which was to take place in the spring, once the snow melted.

When my father did not return I walked toward the field as if it was just another evening, as if nothing had changed. I didn’t know then that my world was about to turn upside down, that it had already become something I was not familiar with, a place I did not know.

I found my father deep in the cornfield. He was lying soaked in his own blood. When I first saw him I couldn’t speak, I couldn’t breathe. Then the blood in my own veins started pumping and I rushed toward him, shouting Baba, Baba, what has happened? He did not speak, and for a moment I thought he wasn’t breathing. Then I bent down and touched him. His skin was wet and cold, and he did not move. I thought he was dead, that my Baba had died, leaving me and my mother and Gulmina to harvest the rest of the corn, leaving us to fight the winter on our own.

Baba opened his eyes after I held his head in my hands and cried, calling him over and over again, looking up at the darkening sky in case that was where he had gone. When he blinked and looked at me I cried even louder, not knowing what was happening. I was so young, you see. Just a small boy.

Baba had stepped on a landmine which took his legs and one hand. He said he was worth nothing now, but my mother held him, shamelessly, and kissed his eyes and his forehead and then offered her prayers to God to thank him for bringing back the father of her children. She wept, but then she wiped her tears and found a sheet to wrap the stumps left behind by the blast. There was so much blood that even the thirsty earth did not absorb it. It was like the blood of the sheep the elders of the village slaughtered for the Festival of the Sacrifice. But this was my father’s blood, my own father, Sangeen Khan, a man made of the hardest rock, broken into pieces like a crushed fruit.

three

October 13, 2002

It has been a good day today. We have managed to sun dry the bricks to perfection (or so Waris tells me, he knows everything) and tomorrow we will begin to rebuild the wall.

Waris took me into the kitchen again to show me something he had hidden behind the door. He was so excited he could hardly speak, and when he did, I barely understood his words, mostly just his gestures, like Qasim the mute when he wants to draw my attention to something. Waris grabbed the shirt Noor Jehan washed for me, making sure it was not infested with lice and other such creatures. He literally pulled me out of the cell this morning. I had barely managed to sleep two nights before, listening to Bulbul’s story.

But this morning I was up with the few birds that still live in these trees—many of them have died or flown away or migrated to the south in search of food and warmth. The handful that still perch on the large tree in the middle of the courtyard sing the sweetest songs, melodies out of tune with the silence of this desert. I watch them sometimes through the bars of this cell and I wonder who they are singing to, and then I remember that they are birds, they are compelled to do things for no good reason at all.

Or perhaps that is reason enough, the silence of this desert.

Waris hit the jackpot, so to speak. He grinned broadly and proudly placed a battered bicycle before me. This was a bike whose handlebars were rusted, the pedals shorn of their rubber, and the mudguards hopelessly dented. But the two tires were there, flat, but nonetheless propped up the miserable machine in defiance of all odds.

I shared the man’s joy and patted the broken seat of the bicycle with glee. Dust rose from it and dispersed into the still, cold air like a whisper.

There is an argument in the kitchen. Waris and Sabir are engaged in an animated discussion, and I can make out only some of it. It appears that both men are eager to get help for the asylum, and now that the bike has been found they are arguing about who gets to ride it to the nearest village. I find this quite laughable, for the nearest village has been bombed too, the homes torched, the people forced to flee. I learned this from Bulbul, he told me about Sarchashma, north of here, across the narrow pass in the mountains.

I am amazed at the optimism both men share. I am equally amazed at how they manage to carry on as if nothing has happened. Waris takes out a small tin of tobacco and offers it to Sabir, who takes a pinch and tucks it into the recesses of his mouth. The men suck on the tobacco as if it was the life force vital to their existence. Maybe that is what I am missing, a pinch of raw tobacco that is spat out in big brown globs once it is drained of its narcotic power.

Bulbul has not come to the kitchen today. I ask Waris if he has seen him. Waris nods and indicates a small trapdoor built into the floor of the kitchen. I am not quite sure what he means—has Bulbul been hiding in the basement? And what is in this basement, this place which is not spoken about openly, referred to only with quiet gestures, as if some abomination has taken place there, some terrible atrocity which cannot be told?

The argument about who gets to ride the bicycle has been resolved. Sabir will take the bike, managing to pedal it with his one leg and the crutch (muddy and cracked though it is). This I have got to see. Waris says the wall will be built tomorrow, after Sabir returns. This is the only way out, and also the only way in.

Sabir is ready to leave now. He wears his shawl wrapped around him like a shroud. And he smiles as he readies himself for the journey, crutch poised elegantly like an athlete’s limb.

Waris accompanies him to the hole in the wall. He embraces this man and places Sabir’s hand over his own heart, bowing his head slightly. The ritual of farewell is so graceful, honoring the last memory you will carry with you on a precarious journey.

Sabir nudges the bike through the hole. He is the lucky one, the one to get away. I have to stay to appease my captors, Waris has to stay to protect the compound, and Bulbul—he has not emerged from the basement since the morning.

In any case he doesn’t want to leave, he told me. And he certainly doesn’t want to go to Sarchashma where his father is buried, and where the earth holds more than the roots of the trees that shelter all living creatures from the sun and the harsh desert light.

October 14, 2002

Sabir is not back yet. I didn’t think he would even get to where he was going on that rickety old contraption, a poor excuse for transport. The sky has darkened; Waris says it is winter rain clouds. He says it is good for the soil, the crops, the animals, who will drink the water collected in the craters littering the landscape. I want to tell him, what about us, what is going to be good for us, but he has already turned his attention to a boil on his leg which looks like it’s about to burst.

I turn away from him. I can see the pus oozing out of that sore, red and swollen with some infection caused by the squalor we live in. I want to tell him, what about water for us, how am I supposed to bathe, how am I supposed to wash this grimy pair of clothes that now brands me as a card-carrying lunatic, the same as everybody else here. But I don’t have the words, and sometimes I believe I don’t even have the will to speak, to wash, to wake up to face another day.

Bulbul took my shorts the day they let me out of the cell—he’d had his eye on them from that first day. God knows what he wants to do with them, a pair of worn-out shorts. He hasn’t returned them. He hasn’t returned to the kitchen either, and I am almost desolate without him.

I turn back to Waris. He has lanced the boil with the sharp point of a long nail which he heated to a red tip on the embers in the grate. The pus oozes out, a river of pale mucus str

eaked with blood. Waris does not flinch; he squeezes the boil until the swelling collapses like a punctured balloon, the mouth of the sore a crater. Then he wipes the sore with the edge of his turban. He turns to the grate and, taking a pinch of ash, he applies it to the sore. I am wondering at this treatment but there must be something in it. After all, these people have survived here for ages without decent medication.

Waris looks at me and smiles, satisfied that he has conquered the beast festering in his leg. Then he rises from the floor and beckons me to follow him. I do so—we move toward the trapdoor and I know that he is finally going to let me enter that space which has been prohibited to me.

I don’t know about this. I really don’t know much about anything anymore. I don’t know what lies hidden in the basement, just as I don’t know what lies hidden in the hearts of these people—my friends, my allies, my enemies.

It was dark in the basement, obviously. There were no windows, no vents. Waris carried a lantern to guide us down the stairs as we felt our way along the uneven stone walls enclosing the space. I could smell the musty odor of something sour, something spoiled. And I could hear Bulbul, whistling in total darkness.

We found him sitting on a burlap sack filled with something, grain perhaps, or flour. He didn’t look up at us. Waris went over and stood before him. I remained by the stairs, wondering why anyone would want to spend time here in this dark, dank room where light and hope and all things good seem to have been kept out. It was colder here than in the kitchen or in the sunlight, the kind of cold that eats into your bones.

No Space for Further Burials

No Space for Further Burials